Originally published in the October 16, 1983 issue of The Times Herald-Record, written by Avice Meehan

Old friends call him Bones. Bones Brennan. Make sure he’s got a pipe in his mouth because when Fred Brennan turns sideways, there’s no other way to tell he’s there.

“We tease him a lot. Jesus, Freddy, we say, you’re putting on a lot of weight. Maybe two pounds in 20 years,” said one long-time acquaintance.

Brennan has friends. He has enemies. He wears, by his own lights, many hats. Sometimes, to an outsider, it’s not clear which hat he’s wearing at a given time, but Brennan is always careful to specify whether he is speaking as newspaper editor, Planning Board chairman, a Recreation Commission member or an ambulance corps volunteer. And speak out he does.

“My opinions are going to be my opinions, regardless of which hat I wear,” said Brennan, conceding that at times the balancing act has been rough. Willing workers, he notes, are not so easy to come by in small towns. And conflicts of interest – as distinguished from conflicts of “personal” interest – are not to be avoided.

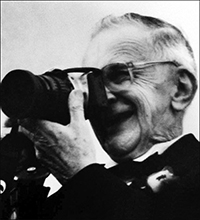

Fred Brennan comes with pipe and camera in hand, rarely one without the other. At 4 a.m., with an apartment building blazing away and the street a tangle of firehoses, Brennan stops for a minute, fiddles with the pipe and then goes on to snap a few shots. As an afterthought in the heat of a still-dark morning, Brennan notices that his pajamas are sticking out from beneath his short-sleeved shirt.

Few events – planned or otherwise – take place in Highland Falls or Fort Montgomery without being noted by Fred Brennan, the 55-year-old editor of The News of the Highlands.

Brennan is a home town guy who lives with his wife, Joan, in the same Lake Street house that belonged to his parents. He went to Sacred Heart Elementary, graduated Highland Falls High, put in an Army stint and after receiving a degree from Syracuse University, came back to Highland Falls to write sports for The News when LeRoy McCormick had the paper.

That was in 1952. Bones came to stay.

The paper was out for the week. Brennan, in theory at least, has a few quiet minutes in the cluttered basement office tucked around the corner from Main Street. A typesetter clacked in the background. He sat, sideways to his desk, awkward at being interviewed, peering through an oversize pair of glasses.

“Being editor in a small town, that’s a unique situation because I’m also a resident,” Brennan mused. “Everything that happens in this community affects me and I’ve never felt when I’ve been at a meeting that everyone else has the right to speak and not me. I can’t just divorce myself.”

Some consider this shy man, once noted for his musical skills, a power broker in the Town of Highlands. Others say he’s overly cautious, looks too long before taking the leap. Still others say he tried to jolt a conservative community into moving too fast. Those who know Fred Brennan say he’s one of a vanishing breed, the kind of editor who until a few weeks ago delivered the papers himself.

Brennan does not consider himself a power broker, though he concedes his editorials may influence a mind or two. To be a power broker, Brennan says, you have to have money and that’s something Fred doesn’t have. At one time he might have had enough money to buy The News. But he didn’t act. The paper passed, in 1969, from the McCormicks to Constantine Sidamon-Eristoff.

“I have never quite made up my mind about Fred,” said Inga Quaintance, who has known him for the better part of 30 years. “He is, very definitely, a guardian of proper procedure, honest to God. I tell you he’s also very opinionated.”

But the outspoken Mrs. Quaintance, who has tangled with Brennan as chairman of the Highland Falls-Fort Montgomery School Board and as the newest member of the Village Board, also has a debt of sorts. She remembers the time Brennan made her cry with an editorial asking her to withdraw her resignation from the School Board. What’s right is right, he told her.

“I don’t think he would ever be subject to external pressures. He is definitely honest and really cares about presenting the public with news,” she said. “He has courage, he has taken up unpopular causes and has been abused and maligned by people.”

One of the great feuds was with the village’s former mayor, King James Weyant, now retired to Florida. Weyant tried to oust Brennan from the Planning Board because he didn’t like the speed with which the board was acting on a proposal for a housing project on Webb Lane. The board, whose members included Weyant’s cousin, Charles Weyant, ultimately approved the project. That was four years ago. The apartments, named for King Jim, opened this summer.

The dispute soured Weyant on Brennan: “He always reported negatively… people are not getting the real, real facts… he doesn’t want to rock the boat.”

Brennan who “never really sought the spotlight,” was left fighting for a traffic light so the old people living in the complex can cross Thayer Road Extension without being run over.

Fred Brennan little imagined that 32 years after graduating from Syracuse University he would be fighting for a traffic light in the town of his birth. No, he admits to grander aspirations. Once he wanted to go into television. Then, he decided on journalism. But the glamor jobs, as he calls them, were scarcer than ambition. He came home, temporarily like.

“I found it more and more difficult to keep thinking that way. I liked what I was doing. I could make a living and, maybe, perform a public service,” he said.

The public service turned, somehow, into a lifetime. A request to help develop a master plan for the Town of Highlands – really, a boring task at first – turned into the work of two decades. Coaching a junior baseball team – the Brennans have no children, just a dog and a passle of nieces and nephews – evolved into another major commitment.

The days spin by. Brennan has met presidents in his day, welcomed the hostages home, seen a new high school. One Sunday there’s a pumpkin contest to be judged in Fort Montgomery. Saturdays there are football games to be covered. Always there are meetings. Brennan admits to moments of discouragement in the midst of it all, but he’s content in his mind.

Highland Falls, today, is scarcely the place of Brennan’s childhood. The field where the Northenders and the Hilltoppers met for baseball is a parking lot. The West Grove School, where Brennan’s mother was a teacher, was swallowed up by the West Point Military Reservation and no longer exists – it’s a shadow, a left hand turn off Route 293 to an empty patch of ground. The field next to his parent’s house now holds three houses. The village boomed, faltered and now, said Brennan, awaits another renaissance.

“It’s home,” Brennan said. “I don’t think it needs any more elaboration than that. I feel for this community just the way I feel for my home, my abode.”